Rated for Fire—But Which Rating, and for Whom?

Post 1 in a series on garage fire separation

The phrase garage wall fire rating shows up in home inspection reports, contractor conversations, building codes, and even casual homeowner discussions—but what it actually means depends on who you ask.

To a home inspector, it might suggest a wall finished in fire-resistant drywall. To a builder, it might refer to a full “fire separation” assembly required by code. A supplier might think of it as the door label on a pre-hung unit. And a homeowner? They might just mean the wall between the house and the garage—the one that “should stop a fire, right?”

That’s the challenge: the language we use to describe fire protection in garages is often inconsistent, and occasionally misleading. In this short series, we’re going to take a closer look—not just at the materials and code requirements, but at the words we use to talk about them. We’ll cover what’s required, what’s misunderstood, and how inspectors can communicate clearly about what they see (and what they don’t).

🔍 Fire Resistance ≠ Fireproof

Let’s begin with a common misconception: nothing in residential construction is “fireproof.” The goal of a fire-rated assembly is not to contain fire indefinitely, but to slow its spread long enough for people to escape and firefighters to respond.

The IRC (International Residential Code) doesn’t refer to “garage firewall” the way commercial codes do. Instead, it requires “separation” between the garage and the house, and describes the materials that must be used to provide that protection. That’s where the confusion begins.

🧱 Glossary of Misused (or Loosely Used) Terms

Here are some of the most commonly tossed-around terms—some official, some not—and how they fit into the garage fire-separation conversation:

Fire-rated wall: A common phrase, but not an official code term in most residential contexts. Often used to describe the wall between the garage and house, especially if it’s clad in Type X drywall.

Firewall: Technically refers to a wall designed to resist fire and remain standing if the structure on one side collapses. Rarely used (or accurate) in residential garage construction.

Fire separation: A more code-aligned term. The IRC requires specific separations between a garage and the living space, which may include walls, ceilings, and doors.

Fire barrier / fire partition: Terms from commercial code (IBC), not typically used in residential construction.

Type X drywall: A gypsum board with additives that increase fire resistance. Required in some locations (e.g., ceilings below habitable space) but not always in walls. It’s important to remember that thickness, installation method, and joint treatment also affect fire resistance.

Demising wall: A wall that separates two distinct living units—like in a duplex or townhouse. Fire-resistance requirements here are significantly higher. We’ll explore this later in the series.

20-minute door / B-label door: Refers to doors with specific fire-resistance ratings. We’ll tackle these in the next post.

🏗️ What the Code Actually Says (IRC Snapshot)

Under the 2021 IRC (and similar in earlier editions), Section R302.5 outlines the required separation between garages and living spaces. Here’s a simplified breakdown:

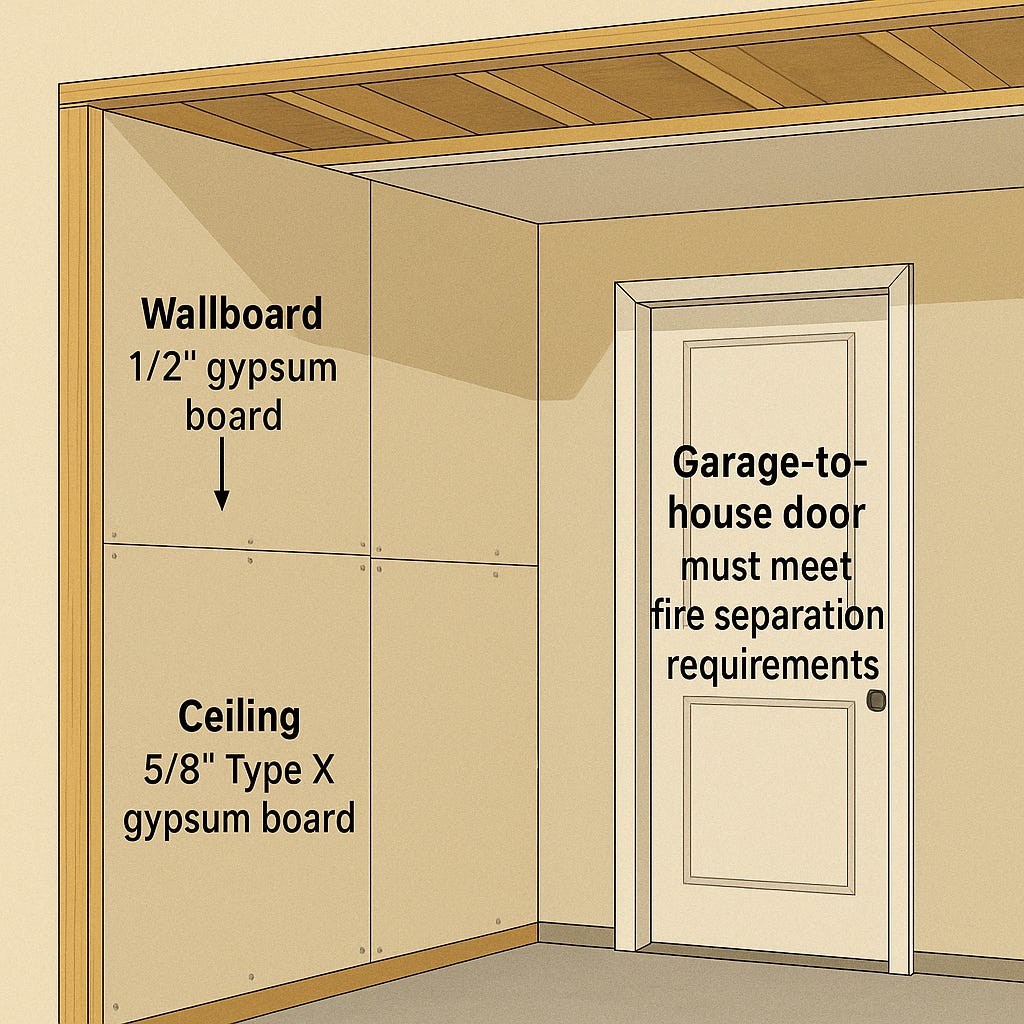

Garage walls adjacent to living space: Must be protected with not less than 1/2" gypsum board applied to the garage side.

Ceilings below habitable rooms: Must be protected with not less than 5/8" Type X gypsum board.

Structural supports (e.g., beams or columns under habitable rooms): Must also be protected.

Door to the house: Must be fire-rated, self-closing, or both (we’ll go deep on this next time).

These are the IRC minimums, but local codes often modify or exceed them.

In some jurisdictions, for example, the use of 5/8-inch Type X drywall on the garage side of the wall is a long-standing requirement—even if the IRC allows 1/2-inch board. Inspectors in those areas may have never seen anything less than 5/8-inch, and rightly so. Over time, regional code amendments and enforcement patterns shape professional expectations. What’s “standard” in one area may be “noncompliant” in another.

It’s a good reminder that inspectors must draw not only on the IRC, but on the local code environment and construction norms they work within. And for those writing reports, it helps to be clear whether you're noting a universal minimum—or something that reflects your jurisdiction’s stricter expectations.

🧠 Why This Matters to Home Inspectors

A typical home inspector doesn’t perform destructive testing, and isn’t responsible for code enforcement. But fire separation between garage and house is a life-safety feature, and worth understanding—because it's often compromised by:

Garage-to-house doors with no label or rating

Drywall removed to add electrical or plumbing, then patched poorly

Missing or damaged ceiling protection under finished rooms

Attic access openings left unsealed or surrounded by combustible framing

An inspector doesn’t need to use commercial-code terms—but should have the vocabulary to describe what’s present, and whether it appears to meet common expectations for garage separation. You don’t have to confirm fire resistance. You just need to observe and communicate clearly.

➡ Coming Next: The Door Between Worlds

In our next post, we’ll focus on the door between the garage and the house—a component whose identity is as fractured as its label.

Homeowners might call it the garage door, the service door, or the man door.

Builders might call it solid-core.

Door suppliers might refer to it by its label—B, C, or 20-minute.

And some inspectors just write: “No visible label.”

But the truth is: the label doesn’t just apply to the slab. It applies to the entire fire-rated door assembly—the slab, the jamb, and often the hardware. A B-label can’t be certified if the slab is installed in an unlisted frame, or if the self-closing mechanism is missing or disabled.

We’ll sort that out in the next post, break down the minimum requirements, and offer some clear language for inspectors writing up what they see. Because just like the wall it sits in, the door—and its frame—deserve more clarity than they’re getting.

Here's a statement I use when I uncover a pet access cut into the fire-rated (20-minute) door.

"A pet door has been installed in the fire-resistance-rated wall separating the attached garage from the home, located adjacent to the laundry room (if that's where it's located). This installation likely breaches the required fire separation (IRC R302.6), increasing the risk of fire and smoke spread and potentially affecting code compliance and insurance coverage. I recommend that a qualified party evaluate this condition for a breach of the fire-rated assembly, as some jurisdictions and insurance companies may require the pet door to be UL-listed."